What is 'germ theory'?

An Odyssey through germ theory – part II

Disclaimer: nothing in this article or other articles is to be taken as medical advice. I am not a doctor, and the information provided here is to be used purely for informational and educational purposes.

If you haven’t done so already, please read part I here.

‘Germ theory’, according to Harvard Library, is the theory that “specific microscopic organisms are the cause of specific diseases”.

These ‘microscopic organisms’ (‘microorganisms’) are also referred to as ‘microbes’ or ‘germs’. The word ‘germ’ is usually used to refer to microbes thought to be ‘pathogenic’ (able to cause disease), but it is, on occasion, used as a ‘catch-all’ to refer to all microorganisms. The word ‘pathogen’, however, is unambiguously used to describe those thought to cause disease.

These microbes can be found just about everywhere and belong to one of five categories; bacteria, viruses, fungi, protozoans or helminths (worms).

Within these categories, we find some that are claimed to be ‘pathogenic’, and responsible for specific diseases. For example, Tuberculosis is said to be caused by the bacteria Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Diphtheria by Corynebacterium diphtheriae. Polio by the poliovirus. And so on.

It is then said that they are able to ‘invade’ an unsuspecting host’s body – usually through ingestion, inhalation or skin contact. And some of these – “less than 1% of bacteria”, according to the Microbiology Society, can, in some cases, cause disease. This idea is quite interesting in itself, because at a deeper level, it creates the narrative that we are in a constant battle with our environment. A recent article published by Imperial College London spells this out clearly for us; “Nature is trying to kill you, but science has your back”.

Being so distinctive, these organisms are said to be ‘monomorphic’, as opposed to ‘pleomorphic’. Monomorphism is one of the key pillars of ‘germ theory’. Each organism is said to be a distinctive entity, endowed with specific capabilities, and will, in some cases, cause specific symptoms in an individual ‘infected’ by it. Pleomorphism on the other hand, refers to the ability of certain microorganisms to alter their morphology, biological functions or reproductive modes in response to environmental conditions, depending on the conditions in which they are placed.

It is the ‘immune system’ then that is said to protect from, and fight off the invading armies. This system is said to be made up of two components; ‘innate’ and ‘acquired’. Put simply, ‘innate immunity’ is that which you are ‘born with’, and includes ‘physical barriers’, such as your skin, that protect your organs from ‘infection’.

‘Acquired immunity’ is just that – ‘immunity’ which one develops or ‘acquires’ after having been exposed to a specific ‘pathogen’, either randomly, or after having been ‘inoculated’, for instance through vaccination.

An individual whose ‘immune system’ isn’t ‘working properly’ is said to to be ‘immunodeficient’. ‘Immunodeficiency’ is defined by the British Society for Immunology as one or more ‘disorders’ that result in “partial or full impairment of the immune system, leaving the patient unable to effectively resolve infections or disease.”

These ‘disorders’ are said to be either:

1.) Primary – “inherited immune disorders resulting from genetic mutations, usually present at birth and diagnosed in childhood” (said to be “the rarer of the two”)

2.) Secondary – “acquired immunodeficiency as a result of disease or environmental factors, such as HIV, malnutrition, or medical treatment (e.g. chemotherapy)”

With some exceptions (e.g. malaria), most diseases thought to be caused by a ‘germ’, are said to be caused by either a bacterium or ‘virus’ (AIDS, Polio, Measles, Rabies, Smallpox, Tuberculosis, Cholera, Diphtheria, etc).

A bacterium is defined by Brittanica as:

“any of a group of microscopic single-celled organisms that live in enormous numbers in almost every environment on Earth, from deep-sea vents to deep below Earth’s surface to the digestive tracts of humans.”

A ‘virus’ is defined as:

“an infectious agent of small size and simple composition that can multiply only in living cells of animals, plants, or bacteria. The name is from a Latin word meaning ‘slimy liquid’ or ‘poison.’”

Unlike bacteria, viruses are not living things. New Scientist writes; “this complete reliability on a host for all their vital processes has led some scientists to deem viruses as non-living”.

They are therefore, really very different, and although they are both ‘microbes’, in order to investigate this topic properly, we really need to look at them in turn. In this article, we will focus primarily on bacteria.

How did ‘germ theory’ come about?

According to Brittanica, the fundamental idea that underpins ‘germ theory’ has been around since ancient times:

“it was expressed by Roman encyclopaedist Marcus Terentius Varro as early as 100 BCE, by Girolamo Fracastoro in 1546, by Athanasius Kircher and Pierre Borel about a century later, and by Francesco Redi, who in 1684 wrote his “Observations on Living Animals Which Are to Be Found Within Other Living Animals”, in which he sought to disprove the idea of spontaneous generation. Everything must have a parent, he wrote; only life produces life.” (note: ‘spontaneous generation’ is the idea that living organisms can develop from nonliving).

In 1762, Marcus von Plenciz, a Slovenian physician based in Vienna, published ‘Opera medico-physica’, in which he described his theory that invisible organisms that he called ‘animalcula minima’ were the cause of infectious diseases. But he was unable to prove it.

In 1860, the world-famous British nurse, Florence Nightingale, wrote in her book, ‘Notes on Nursing’:

“Diseases are not individuals arranged in classes, like cats and dogs, but conditions, growing out of one another.

Is it not living in a continual mistake to look upon diseases as we do now, as separate entities, which must exist, like cats and dogs, instead of looking upon them as conditions, like a dirty and a clean condition, and just as much under our control; or rather as the reactions of kindly nature, against the conditions in which we have placed ourselves?

I was brought up to believe that smallpox, for instance, was a thing of which there was once a first specimen in the world, which went on propagating itself, in a perpetual chain of descent, just as there was a first dog, (or a first pair of dogs) and that smallpox would not begin itself, any more than a new dog would begin without there having been a parent dog.

Since then I have seen with my own eyes and smelled with my own nose smallpox growing up in first specimens, either in closed rooms or in overcrowded wards, where it could not by any possibility have been ‘caught’, but must have begun.

I have seen diseases begin, grow up, and turn into one another. Now, dogs do not turn into cats.

I have seen, for instance, with a little overcrowding, continued fever grow up; and with a little more, typhoid fever; and with a little more, typhus, and all in the same ward or hut.

Would it not be far better, truer, and more practical, if we looked upon disease in this light?

For diseases, as all experience shows, are adjectives, not noun-substantives.”

This passage suggests that the fundamental tenets of ‘germ theory’ were widely known, but had not been accepted as correct. Harvard Library writes:

“[germ theory] encouraged the reduction of diseases to simple interactions between microorganism and host, without the need for the elaborate attention to environmental influences, diet, climate, ventilation, and so on that were essential to earlier understandings of health and disease …

Because of this, some important proponents of hygiene and sanitation—including Florence Nightingale and Rudolf Virchow—did not necessarily believe that acceptance of the germ theory would be associated with improvements in public health.”

So what changed?

The discovery of the process of fermentation

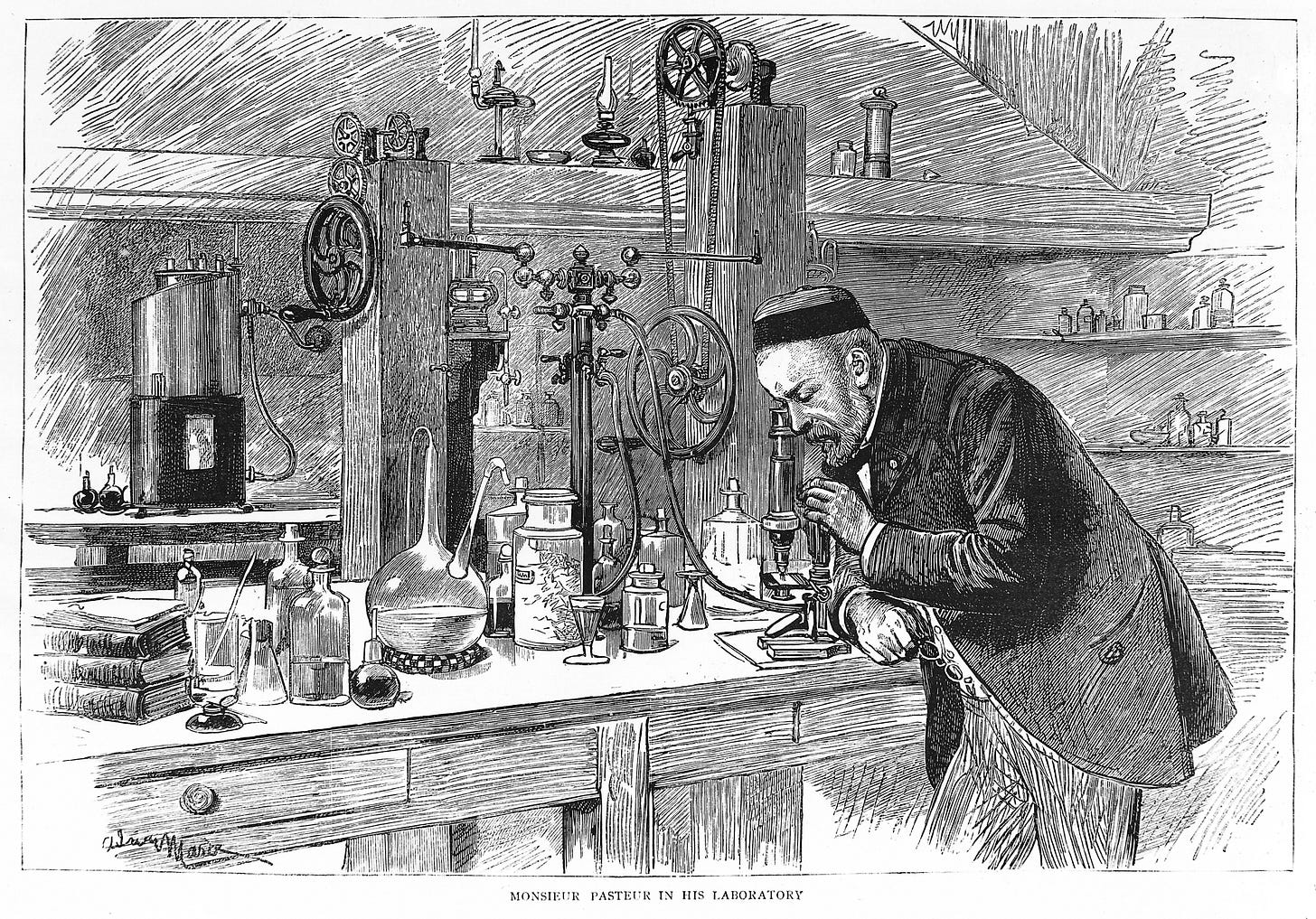

Fermentation is described by Britannica as a process whereby “molecules such as glucose are broken down anaerobically (without oxygen)”. This discovery is usually credited to Louis Pasteur (1822 – 1895), who also allegedly discovered how this process could not take place without the presence of microorganisms: “it was Pasteur who, by a brilliant series of experiments, proved that the fermentation of wine and the souring of milk are caused by living microorganisms.”

Louis Pasteur was a french chemist and it is both he, and the german Robert Koch (1843 - 1910), who by and large are said to be the individuals that proved ‘germ theory’ to be correct: “Koch and Pasteur independently provided definitive experimental evidence that the anthrax bacillus was indeed responsible for the infection. This firmly established the germ theory of disease, which then emerged as the fundamental concept underlying medical microbiology.”

Pasteur’s work on fermentation, however, was heavily influenced by by the work of one of his contemporaries, Antoine Béchamp (1816 – 1908) (and some in fact accuse him of plagiarising Béchamps’ work).

Béchamp began researching fermentation in 1854. His ‘Beacon Experiment’ proved that molds accompanying fermentation contained living organisms, and that this transformation could not have taken place without contact with the air. He eventually discovered that these organisms could be found just about everywhere, and he named them ‘les microzymas’ (the ‘microzymas’).

Although he didn’t initially agree with Béchamp’s findings, Pasteur, who had previously held the position that such a phenomenon could only be explained by ‘spontaneous generation’, went on to carry out similar experiments. Both his and Béchamp’s body of work are meticulously documented in Ethel Hume’s excellent book, Béchamp or Pasteur (a must read for anyone interested in this topic).

After emulating Béchamp’s experiments, Pasteur eventually came to accept that fermentation was indeed, caused by the ‘germs’ contained in the air. In his essay published in the British Medical Journal in 1876, neurologist Dr Henry Charlton Bastian wrote:

“it was not till twenty years after [the discovery of the yeast-plant] that Pasteur announced, as the result of his apparently conclusive researches, that low organisms acted as the invariable causes of fermentations and putrefactions – that these, in fact, though chemical processes, were only capable of being initiated by the agency of living units.”

It was now widely recognised that these microorganisms existed, but there was no evidence that they caused disease - in fact, Béchamp’s work proved quite the opposite. In the book ‘Pasteur: Plagiarist, Impostor’ (included as a preface to the aforementioned book authored by Hume), Pearson writes:

“In innumerable laboratory experiments, assisted now by Professor Estor – another very able scientist – he found microzymas everywhere, in all organic matter, in both healthy tissues and in diseased, where he also found them associated with various kinds of bacteria.

After painstaking study they decided that the microzymas rather than the cell were the elementary units of life, and were in fact the builders of cell tissues. They also concluded that bacteria are an outgrowth, or an evolutionary form, of microzymas that occur when a quantity of diseased tissues is broken up into its constituent elements.

He proved that on the death of an organ its cells disappear, but the microzymas remain, imperishable.

When he again found bacteria in the remains of the second experiment, as he had in the first, he concluded that he had proved, because of the care taken to exclude airborne organisms, that bacteria can and do develop from microzymas, and are in fact a scavenging form of the microzymas, developed when death, decay, or disease cause an extraordinary amount of cell life either to need repair or be broken up.”

Béchamp himself wrote in 1869:

“In typhoid fever, gangrene and anthrax, the existence has been found of bacteria in the tissues and blood, and one was very much disposed to take them for granted as cases of ordinary parasitism. It is evident, after what we have said, that instead of maintaining that the affection has had as its origin and cause the introduction into the organism of foreign germs with their consequent action, one should affirm that one only has to deal with an alteration of the function of microzymas, an alteration indicated by the change that has taken place in their form.”

Béchamp also carried out experiments with grapes that demonstrated that these microorganisms were not only found in the air, but also on, and within more complex organisms, and that changes made to the environment could still cause fermentation. Dr Bastian describes this finding as follows:

“Grapes, for instance, suspended in an atmosphere of carbonic acid, will undergo fermentation, so as to generate alcohol and other products, even without the presence of torulae [yeast] or allied organisms. Other fruits and vegetables treated in the same way behave more or less similarly. Organic multiplication of independent organisms has therefore now been shown, by Pasteur himself and his followers, not to be an essential factor in the process of fermentation”.

Pasteur once again, did not agree with these findings, but eventually came around, and made changes to his own theory. Dr Bastian writes:

“Pasteur has, within the last two years, made a most important modification in his theory of fermentation. Whilst he formerly held that fermentation and putrefaction are chemical processes initiated by independent organisms (bacteria and their allies), and taking place in correlation with their growth and multiplication, he has of late shown that similar phenomena may be initiated by the chemical processes taking place in the tissue-elements of certain fruits and vegetable tissues, when these are placed under certain abnormal conditions”

When Pasteur eventually came to accept these facts, he hypothesised, like Pleniz and others before him, that specific types of fermentation were caused by specific organisms, and thus that they must also be the cause of specific diseases. In the final report made to the Royal Commission on Vivisection, Dr. C. J. Martin of the Lister Institute is reported to have said: “His [Pasteur’s] experience on this subject (fermentation) led him to the great generalisation that infectious diseases might themselves be interpreted as particular fermentations and as due to specific micro-organisms.”

As we previously discussed, it isn’t hard to see why Pasteur’s theory would have been ‘preferred’ over Béchamp’s. Specific microorganisms causing specific diseases means specific treatments need to be developed.

Today, Béchamp, despite his incredible achievements and discoveries, has been completely sidelined, his work by and large, buried, and is often referred to in disparaging ways, such as in this article where he is labelled a “bitter crank”.

Pasteur eventually came to agree with virtually all of Béchamp’s findings. So why is Béchamp’s work ignored? The reason is a simple one; Pasteur thought these were distinct entities, capable of causing disease, whereas Béchamp saw them as a consequence of disease, itself caused by other factors.

So was Pasteur right? Let’s take a look at the evidence.

How do we know that ‘germs’ cause disease?

Carl Sagan once proposed that “extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence”.

In the aforementioned essay, Dr Bastian wrote; “Bacteria … do nevertheless habitually exist in so many parts of the body in every human being, and in so many of the lower animals, as to make it almost inconceivable that these organisms can be causes of disease.”

This echoes what Béchamp had previously written: “if virulent [hostile] germs were normal in the atmosphere, how numerous would be the occasions for their penetration independently by way of the lungs and intestinal mucus! There would not be a wound, however slight, the prick even of a pin, that would not be the occasion for infecting us with smallpox, typhus, syphilis, gonorrhoea.”

And indeed, when you think about it, the notion that we are surrounded by an incalculable number of these organisms, and that some could cause harm, is really quite bizarre, and somewhat counterintuitive.

Because this is such an extraordinary claim, the onus is on the ‘germ theorists’, to prove beyond reasonable doubt, that their theory stacks up – not the other way round. And it’s a tough ask, because unlike certain chemicals or other substances that are known to cause disease when ingested or inhaled (e.g. mercury), bacteria, as Dr Bastian wrote, are always there.

The latin phrase ‘Cum hoc ergo propter hoc’ means ‘with this, therefore because of this’ or in more familiar terms ‘correlation does not equal causation’. This describes a logical fallacy that suggests that if two events happen at the same time, or one after the other, then one must cause the other. For example, one habitually finds flies near or around rubbish. Such a fallacy would be to conclude that the flies created the rubbish.

To avoid this pitfall, it becomes imperative to devise a sound methodology to prove cause and effect. In an article published in 1884 on the aetiology (causality) of tuberculosis, Koch wrote; “it is not sufficient to establish only the concomitant [naturally accompanying] occurrence of disease and parasite but the parasite must be shown to be the real cause”.

Such a test was devised by Koch’s assistant Friedrich Loeffler. These are known as ‘Koch’s Postulates’; a set of principles to help establish causation when investigating ‘pathogens’. They are as follows:

The same organism must be present in every case of the disease.

The organism must be isolated from the diseased host and grown in pure culture.

The isolate must cause the disease, when inoculated into a healthy, susceptible animal.

The organism must be re-isolated from the inoculated, diseased animal.

As a side note, it was later claimed that these postulates could not be used when investigating ‘viruses’. In 1932, virologist Thomas Rivers modified these principles (known as ‘Rivers Postulates’). He wrote; “It is obvious that Koch’s postulates have not been satisfied in viral diseases”. We will revisit this when we look at ‘viruses’.

Koch’s Postulates are generally referred to as the ‘gold standard’. However, as we shall see, the criteria were never really satisfied, even at the time. Hume, referencing a 1909 article in The Lancet writes: “Koch’s postulates are rarely, if ever, complied with.”

And this is still the case today, and we are also told that it doesn’t actually mater. Take for example the following article written by Reuters ‘fact checkers’, where they say: “Koch’s postulates, as they were originally understood, do not need to be demonstrated in order to establish that a microbe causes a disease.”

And apparently, this is because “virus research has been transformed by genetic techniques developed decades after Koch’s death”.

But really, the test is one of simple logic. Modern techniques are irrelevant because the logic should stand up to scrutiny, irrespective of any such techniques. Furthermore, anyone should be able to understand these principles and assess whether or not, when applied correctly, they are able to provide satisfactory evidence of the claims being put forth.

And no doubt, this is why attempts are made to discredit these. As we will see, when the postulates are applied correctly, we find that they are unable to prove the claims being made – in fact, they disprove them.

The problem of ‘asymptomatic carriers’

Unfortunately, Koch and his disciples do not appear to have anticipated the problem of ‘asymptomatic carriers’, first found in cholera, and later typhoid fever, which resulted in Koch abandoning the first postulate altogether. And this is where the wheels start to come off.

Koch’s student, Loeffler, who originally devised these principles, also ran into problems when attempting to prove that the disease known as diphtheria was caused by a specific bacteria. He was only able to find the bacteria in approximately 60% of the cases he was presented with:

“He was able to demonstrate diphtheria bacilli in smears of only 13 out of 22 cases of clinical diphtheria. From six of these he isolated Corynebacterium diphtheriae. He isolated diphtheria bacilli from one normal child. Because of the lack of a one-to-one correlation in these findings, he was not adamant in claiming to have established the etiology of the disease.”

Remarkably however, the author of this paper goes on to say: “but he had in fact clearly established its etiology. From the time of Loeffler, it has been evident that harboring diphtheria bacilli is not synonymous with diphtheria and that Koch’s postulates cannot be fulfilled in every case of diphtheria. Loeffler’s experimental infections in animals led to the discovery that diphtheria bacilli tended to remain at the site of injection, although autopsy revealed damage to organs far from that site.”

Another example is provided to us by Hume, quoting Sternberg’s Text Book of Bacteriology: “the demonstration made by Ogston, Rosenbach, Passet and others, that micrococci are constantly present in the pus of acute diseases, led to the inference that there can be no pus formation in the absence of microorganisms of this class. But it is now well established by the experiments of Crawitz, de Bary, Steinhaus, Scheurlen, Kaufmann and others that the inference was a mistaken one, and that certain chemical substances introduced beneath the skin give rise to pus formation quite independently of bacteria.”

‘Asymptomatic carriers’ are in fact, the norm for virtually all diseases said to be caused by bacteria, or any other ‘germ’. Wikipedia have a short page where they discuss this matter, and Typhoid fever, HIV, Epstein-Barr, Polio, Cholera, Chlamydia and Tuberculosis are all mentioned. But this list is by no means exhaustive. Take for example Gonorrhea. The CDC writes: “many men with gonorrhea are asymptomatic” and “most women with gonorrhea are asymptomatic”.

So if the first postulate is dropped, this can only confirm one thing; that the ‘pathogen’ on its own cannot cause disease. If it could, then there would be no such thing as ‘asymptomatic carriers’. Evidently, other factors play a role.

Let’s take a closer look at the third postulate. Some texts – for example, Essentials of Microbiology will recant it as follows: “the cultured microorganism should cause disease when introduced into a healthy organism.”

Others, such as the original text I cited, will sometimes also include the word ‘susceptible’: “the isolate must cause the disease, when inoculated into a healthy, susceptible animal.”

What does ‘susceptible’ mean? The CDC writes: “the final link in the chain of infection is a susceptible host. Susceptibility of a host depends on genetic or constitutional factors, specific immunity, and nonspecific factors that affect an individual’s ability to resist infection or to limit pathogenicity.”

‘Specific immunity’ is a euphemism for ‘acquired immunity’. Nonspecific factors refer to ‘innate immunity’ (the skin, mucous membranes, gastric acidity, cilia in the respiratory tract, the cough reflex etc).

The CDC also state that certain factors may “increase susceptibility”, and these are the same as those cited by the British Society of Immunology in their definition of ‘secondary immunodeficiency’ (which if you recall, is unequivocally stated to be the most common ‘type’).

It follows then, that you cannot therefore have a test subject that is both ‘healthy’ and ‘susceptible’.

Some will argue that one could theoretically be healthy and ‘susceptible’ – in the same way that one can be healthy and ‘sensitive’ to alcohol or caffeine. They’re healthy, but lack ‘specific immunity’ – in other words they are unable to produce the specific ‘antibodies’ needed to fight the specific ‘pathogen’.

However this explanation doesn’t align with what we’re told, about, for example, Tuberculosis. The NHS state that:

“In most healthy people, the body's natural defence against infection and illness (the immune system) kills the bacteria and there are no symptoms. You will not have any symptoms, but the bacteria will remain in your body. This is known as latent TB. If the immune system fails to kill or contain the infection, it can spread within the lungs or other parts of the body and symptoms will develop within a few weeks or months. This is known as active TB.

Latent TB could develop into an active TB disease at a later date, particularly if your immune system becomes weakened.”

At no point, do they talk about ‘specific antibodies’ or prior exposure. They are simply talking about your general state of health; if you are healthy, your ‘immune system’ will function as they claim it should, and “kills the bacteria”. If you become unhealthy, it no longer will (according to them) And this is further confirmed by the fact that we are told that Tuberculosis is one of the ‘opportunistic infections’ caused by a weakened ‘immune system’, such as that which is said to result from an alleged HIV ‘infection’ (as discussed previously, ‘immunosuppression’ is not a condition that is exclusive to an alleged HIV ‘infection’).

The third postulate is clearly a contradiction, and therefore it cannot prove cause and effect, unless the first postulate is reinstated and we do away with the concept of ‘asymptomatic carriers’.

And this would still be the case, even if we drop the word ‘susceptible’. If a perfectly healthy, ‘non-susceptible’ organism is ‘infected’ with the pathogen, and remains well, then other factors are a play.

So why leave it in? Simply, because this is the one that, even if you ignored all the others, could be claimed to prove causation – which is really the crux of the matter. If causation cannot be proved, then the whole thing falls apart.

Some will then say; “but Pasteur, Koch and others were able to cause disease in their test subjects. Doesn’t then fulfil the postulates and prove causality?”

This is a good question, but the devil is in the detail. Invariably, one finds that in these experiments, they will inject the ‘pathogen’ into their test subject. Take for example, Koch’s anthrax experiment, described here (‘inoculation’ in this context means injection):

“He discovered that inoculating a mouse with blood from a sheep that had died of anthrax caused the mouse to die the following day. At autopsy, rod-shaped structures were present in the blood, lymph nodes, and spleen. Inoculation of a second mouse with splenic blood from the first mouse produced the same result. By repeating these inoculations, Koch could propagate anthrax rods over dozens of generations.”

Given that it it widely accepted, by Pasteur himself and his followers, that these microorganisms can be found in the air itself, it ought to be possible to isolate them from here. Hume writes:

“Here we see the basic theory of the airborne disease germ doctrine contradicted by the last postulate; for if to invoke disease, organisms require to be taken from bodies, either directly or else intermediately through cultures, what evidence is adduced of the responsibility of invaders from the atmosphere?”

Anthrax is actually one such ‘pathogen’ that is said said to not be contagious. According to the CDC, infection can happen when either breathing in spores, eating food or drinking contaminated water, or coming into contact with these spores through a cut or scrape in the skin.

So the next question then is this; why is it that Koch and others insist on injecting the materials into their test subjects, rather than try to emulate what he and others claim takes place outside of their laboratories?

It’s also never entirely clear why they almost always choose to use secretions from one species of animal, which they will then inject into another. This is very odd, particularly given the fact that it is known that this can in of itself, cause certain problems. Even Wired Magazine acknowledges this:

“Subsequent transfusions using sheep's blood were not as successful, however, and the practice was eventually banned. Science was unaware of the danger not only of interspecies transfusions but of the fact that human beings possessed different, generally incompatible, blood types.”

And finally, if blood, other bodily fluids or tissue are being injected, then it is obvious that the ‘pathogen’ itself has not been isolated (we will discuss isolation more in a future article).

Suppose then that the sheep the blood was taken from, had in fact been poisoned. Said poison would logically then also be found in its blood, and therefore by injecting the mouse, as he did, Koch would have also not only transmitted the alleged ‘pathogen’, but also, the poison – and this doesn’t seem all that farfetched when one considers what anthrax may in fact be.

Sally Morrell has written an excellent article on this subject, which I thoroughly recommend reading. In it, she writes:

“Let us consider sheep dip. The world’s first sheep dip was invented and produced by George Wilson of Coldstream, Scotland in 1830—it was based on arsenic powder. One of the most successful brands was Cooper’s Dip, developed in 1852 by the British veterinary surgeon and industrialist William Cooper. Cooper’s dip contained arsenic powder and sulfur. The powder had to be mixed with water, so naturally agricultural workers—let alone sheep dipped in the arsenic solution–sometimes became poisoned.“

The symptoms of arsenic poisoning are remarkably similar to those of “anthrax,” including the appearance of black skin lesions. Like anthrax, arsenic can poison through skin contact, through inhalation and through the gastro-intestinal tract. If an injection contains arsenic, it will cause a lesion at the site.”

She concludes with the following:

“scientists have found that certain bacteria can “bioremediate” arsenic in the soil. These arsenic-resistant and/or accumulating bacteria “are widespread in the polluted soils and are valuable candidates for bioremediation of arsenic contaminated ecosystems.” Nature always has a solution, and in the case of arsenic, the solution is certain ubiquitous soil bacteria. We need to entertain the possibility that the “hostile” anthrax bacteria, first isolated by Robert Koch, is actually a helpful remediation organism that appears on the scene (or in the body) whenever an animal or human encounters the poison called arsenic.”

To conclude

Everything I have included above laid the groundwork for the claims made by ‘germ theory’. Today, researchers are no longer asking the question ‘do bacteria cause disease?’ It is a given – an axiom the underpins everything else. The medical literature, the curriculums – everything is based on this erroneous assumption.

It is a theory that is riddled with contradictions and inconsistencies. The ‘gold standard’ test itself, is never used in practice, which in itself, should be a red flag.

The logic that Loeffler put forth is sound, but reality had other ideas. In normal circumstances, this would lead to a re-evaluation of the hypothesis being tested. But instead, they simply shifted the goalposts.

Suppose then that we had no other explanation(s) available to us for why people get sick. In this hypothetical scenario, we could perhaps say; we are not able to demonstrate causality, but this is the only explanation we’ve got so let’s stick with it.

But that isn’t the case here.

In every case I’ve looked at, you find, that there is a perfectly reasonable explanation for why people and / or animals are getting sick. See for example the article I wrote on HIV / AIDS or the threads on polio and rabies. Sally’s aforementioned article on anthrax is also very much worth reading.

Unfortunately, most people simply believe ‘germ theory’ to be true because they have been told it is so, since the day they were born. Béchamp writes:

“The general public, however intelligent, are struck only by that which it takes little trouble to understand. They have been told that the interior of the body is something more or less like the contents of a vessel filled with wine, and that this interior is not injured – that we do not become ill, except when germs, originally created morbid, penetrate into it from without, and then become microbes.

The public do not know whether this is true; they do not even know what a microbe is, but they take it on the word of the master; they believe it because it is simple and easy to understand; they believe and they repeat that the microbe makes us ill without inquiring further, because they have not the leisure – nor, perhaps, the capacity – to probe to the depths that which they are asked to believe.”

Béchamp makes a good point here – trying to get to the bottom of things, in this field is not easy, and takes up a considerable amount of time and effort. My hope is that articles like this can provide a good entry point for those who doubt the official narrative.

As always, thank you for reading this, and if you found it interesting, please do share it with others.

In the next article, we will be taking a closer look at ‘viruses’.

Sebastien, in this article, you touched on the idea that our bodies are always fighting bacteria, fungi, and viruses. I think about that too. If that were the case, we'd all be dead. Or we would have never been here. There is no way that our bodies could make white blood cells fast enough and for long enough to overtake the unlimited supply of these "pathogens". B.J. Palmer, one of the first chiropractors is famous for saying, "If the “Germ Theory of Disease” Were Correct, There’d Be No One Living to Believe It". And think about it, bacteria and fungi were on this earth long before human. If they attacked us, we would have never made it to this multi celled organism. The fact is that Bechamp is right, bacteria and fungi, are here to help us. They eat diseased tissue. Ever see fungus consume a fallen dead tree in the forest. Yes. Ever see fungus kill a live tree. No. When I subscribed here, I fully expected to subscribe for the standard $5. Might be time to add that feature. :) Keep up the good work.

So happy to have found your Substack through Amandha Vollmer!