Disclaimer: nothing in this article or other articles is to be taken as medical advice. I am not a doctor. The information provided here is purely for informational and educational purposes.

If you haven’t done so already, please read the introduction to ‘germ theory’. In this article, we will be taking a closer look at what ‘viruses’ are, why they are thought to cause ‘disease’, and how this is said to be demonstrated.

What is a ‘virus’?

According to Britannica, a ‘virus’ is defined as “an infectious agent of small size and simple composition that can multiply only in living cells of animals, plants, or bacteria. The name is from a Latin word meaning ‘slimy liquid’ or ‘poison’.”

Examples of texts making use of this word – ‘vīrus’ – are hard to come by, but one such example is provided in the form of a pamphlet published in 1599 titled ‘Master Broughton’s Letters’, in which the author writes: “you have spent all the vires and power you have for the defence of a vain paradox, and spit out all the virus and poison you can conceive”.

Assuming this word was indeed used in the way we’re told it was, an important question immediately comes to mind; how did it come to be redefined?

The first ever ‘virus’ – the ‘tobacco mosaic virus’ – was discovered by Dutch microbiologist Martinus Beijerinck in 1898. Some say it was he who redefined the word; “Beijerinck, in 1898, was the first to call ‘virus’, the incitant of the tobacco mosaic”.

However, I have been unable to find any primary source materials to confirm the veracity of this statement, and most secondary sources merely state that he referred to his discovery as ‘contagium vivum fluidum’ (‘contagious living fluid’). The word ‘virus’ is never mentioned.

Why this matters will become clear later on. For now, just remember this; we are told, that this word was once understood to mean ‘poison’.

This once novel concept refers to particles, small enough to be filtered through a ‘chamberland filter’; a porcelain water filter able to hold back bacteria. These particles are made up of a DNA or RNA ‘core’, enveloped by a ‘shell’ – called a ‘capsid’, itself made of protein. Some are also said to have an ‘outer shell’ – known as an ‘envelope’. These are referred to as ‘enveloped viruses’.

Once inside a ‘host’ organism, these particles ‘latch on’ to cells, work their way in, and then essentially ‘trick’ them into making more ‘viruses’. Thus, the objective of any given ‘virus’ is to replicate – as the Microbiology Society puts it: “viruses only exist to make more viruses.”

After replication, the ‘viruses’ exit the host cell – either through ‘budding’ or ‘lysis’ (cell death). The new ‘virus’ particles (‘virions’) then move on to the next cell. Thus, a ‘virus’ needs a host cell in order to replicate. The Microbiology Society writes: “they [viruses] are unique because they are only alive and able to multiply inside the cells of other living things.”

The exact mechanism used by these ‘viruses’ to enter cells, does however, seem to vary. For instance, in the case of SARS-CoV-2, we are told that “the mechanisms through which this virus takes control of an infected cell to replicate remains poorly understood.”

Interestingly, these particles are also said to not be ‘alive’ – which then begs the question; how can something that is not ‘alive’, be ‘killed’?

There are a great many ‘viruses’ out there – 10 nonillion, according to this article. Thankfully, most of them pose no threat to human health.

Some, however, are said to be ‘pathogenic’ (disease-causing). But what are these claims based on?

Making epidemiological observations

According to the BMJ, epidemiology is “the study of how often diseases occur in different groups of people and why”. The why is what we will be focusing on.

Epidemiological observations do not automatically prove that one is dealing with an ‘infectious agent’. For example, being in the same room as a sick person, and subsequently developing similar symptoms, does not prove (or disprove) anything.

Scurvy, beriberi and pellagra are all said to be different ‘diseases’ caused by ‘nutritional deficiencies’ (although it would appear this is another big myth). Over the years, various ‘mystery diseases’ have popped up and been linked to widespread poisoning – the Minamata bay disaster, ‘Itai-Itai disease’, ‘Yushō disease’, or the Spanish ‘toxic oil syndrome’, all provide examples of situations where epidemiological observations were made, but ‘viruses’ and bacteria were absolved of any responsibility.

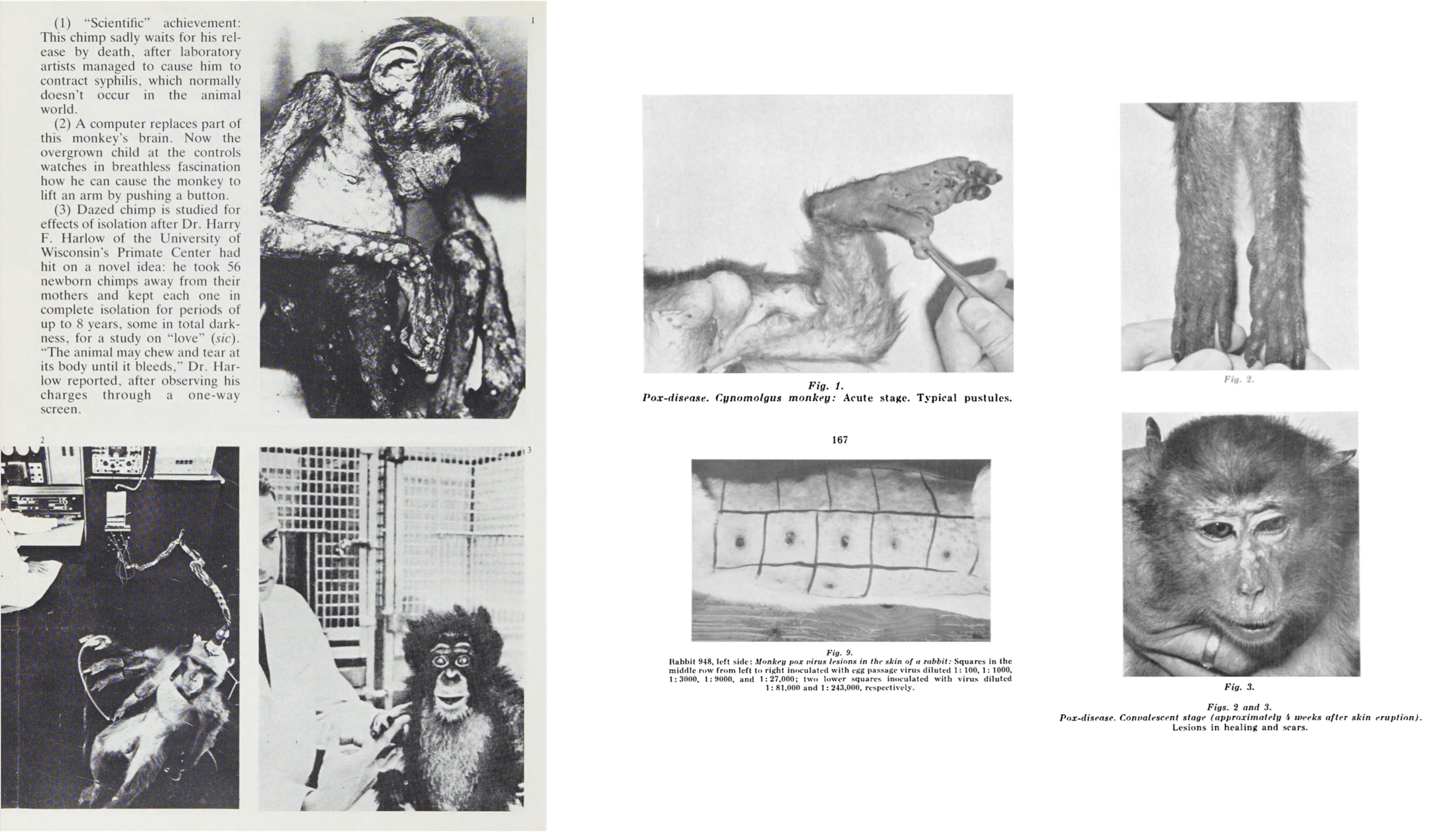

‘Sheep dipping’ is a practice whereby farmers dip their sheep into various toxic substances in order to ‘protect’ them from parasites. The practice continues to this day. The first sheep dip – Cooper’s Dip, was invented in 1852. Its ingredients primarily consisted of arsenic and sulphur. As of today, the UK appears to have abandoned the use of arsenic, but other similarly toxic substances are now used in its place, exposure to which sometimes result in symptoms that are remarkably similar to those of ‘polio’ and other ‘neurological disorders’ said to be caused by a plethora of ‘viruses’.

In places like Iran, it would appear that arsenic continues to be used in this capacity. Interestingly, the highest concentration of arsenic in sheep is found in their wool – and this is perhaps why the CDC recommends that protective gear be worn when ‘handling’ animals, in regards to ‘anthrax’.

In the 18th century, arsenic was used everywhere; as a treatment for various ‘diseases’, but also in dresses and even in wallpaper. In 1862, a few months after a worker in the fashion industry died of arsenic poisoning, the following cartoon titled ‘The Arsenic Waltz’ was published, alluding to the use of arsenic in dresses and artificial flowers.

Arsenic was also used to preserve dead bodies. In 1838, physician John Snow wrote a letter published in The Lancet, where he wrote about the dangers of this practice, and how it could “expose the dissector to breathe an atmosphere contaminated with arsenuretted hydrogen, which is, perhaps the most deadly combination of arsenic”. And in the US, until only recently, the arsenic-based drug roxarsone was added to chicken feed in order to help them gain weight (this practice continues to this day in certain countries).

In the case of so-called ‘sexually transmitted diseases’, we find that “it has long been established that agents such as arsenic and cadmium which are known reproductive toxicants are found to accumulate in human semen [Gagnon 1988]”.

An individual who has been irradiated will become radioactive – hence why individuals in this situation are subjected to a decontamination process. But even lower doses of radiation can be problematic; those treated with radioactive iodine are told to “stay a distance of at least 6 feet away from others”.

In the 90s, pesticide ‘malathion’ (which the EPA has linked to a whole range of symptoms that are remarkably similar to those of ‘polio’), was sprayed by helicopter over Los Angeles, in an effort to combat ‘medfly’. And just a few years ago, a team of researchers suggested that the ‘disease’ caused by ‘zika virus’, is in fact likely to be linked to the widespread spraying of insecticide ‘Pyriproxyfen’.

The point is this; one or more people can be simultaneously exposed to one or more toxins in much the same way that we are told they can be exposed to ‘viruses’. As a result, some may get sick, and those who do may exhibit similar symptoms. But as the the examples documented above clearly show, this doesn’t mean ‘viruses’ or bacteria have anything to do with it.

What it does mean, is that a great deal of what we’re told about about how ‘viruses’ and bacteria ‘spread’ can also be said for poisons. Pesticides for instance, can be ‘airborne’, and will eventually find their way into the water supply. This article published in 2013 mentions how “hundreds of vultures in Namibia died after feeding on an elephant carcass that poachers had poisoned ... in Mozambique three lions died after eating bait infused with a crop pesticide."

Remember; we’ve been told that the word ‘virus’ was once understood to mean ‘poison’.

If poisons are involved, then why do not all people get sick?

There are a great many factors that come into play – the type and length of exposure, the dose, the general state of health of the individual. Taking the example of mercury; “human toxicity varies with the form of mercury, the dose and the rate of exposure.”

Charles Richet, the discoverer of the phenomenon known as ‘anaphylaxis’, made the following statement in his Nobel prize acceptance speech: “every living being, though presenting the strongest resemblances to others of his species, has his own characteristics so that he is himself and not somebody else.”

An individual exposed to a toxin may eventually adapt to it – the consumption of drugs – including alcohol, is a good example. Cigarettes are another. Smokers who stop smoking sometimes develop a cough; the body, ‘sensing’ that it is no longer being exposed to toxins, attempts to rid itself of those that have accumulated over time.

Our society has been led to believe that symptoms are the ‘disease’ – and that if the symptoms go away, so too does the ‘disease’. But as Dr John Tilden, wrote in his book: “so-called disease is natures' effort at eliminating the toxin from the blood. All so-called diseases are crises of Toxemia.”

All manner of drugs are taken to suppress these symptoms – Calpol, to take just one example. And often, drugs are taken to counteract the ‘side effects’ of those taken to ‘treat’ the original ailment. Now, what happens if the symptoms are suppressed, but exposure to the ‘source of enervation’ as Tilden calls it, continues? He writes:

“But the disease was not cured; for the cause (enervating habits) is continued, toxin still accumulates, and in due course of time another crisis appears.”

Such a ‘crisis’ may manifest in the form of cancer:

"If wrong eating is persisted in, the acid fermentation first irritates the mucous membrane of the stomach; the irritation becomes inflammation, then ulceration, then thickening and hardening, which ends in cancer at last."

What is the purpose of a fever, a cough, or a rash? We’ve been led to believe these ‘symptoms’ simply exist to make us feel bad, but clearly, such phenomena serve a different purpose altogether.

Florence Nightingale, the world-famous nurse, expressed similar views in her book, ‘Notes on Nursing’, in which she wrote; “all disease, at some period or other of its course, is more or less a reparative process ... an effort of nature to remedy a process of poisoning or decay, which has taken place weeks, months, sometimes years beforehand..”

Nightingale explicitly rejected ‘germ theory’; a paradigm that is rooted in the idea that unique, ‘infectious agents’, are responsible for specific ‘diseases’ that are usually said to have a ‘distinctive feature’ – and of course, a specific ‘cure’. She wrote; “I have seen diseases begin, grow up, and pass into one another. Now, dogs do not pass into cats.” And indeed, we find that symptoms said to be ‘unique’, are not.

Let’s look at a few examples.

How do different ‘viruses’ compare?

Virologist Thomas Rivers, in his paper on ‘chickenpox’ stated the following:

“a few investigators have claimed that streptococci are the inciting agent of poliomyelitis ... consequently, they wonder why streptococci are not more generally accepted as the cause of infantile paralysis. The reason for lack of general acceptance is a simple one; the disease produced in the experimental animals is not poliomyelitis. Paralysis is not a characteristic sign of a single disease...”

Here, a leading virologist is explicitly telling us that the ‘feature’ said to be characteristic of a ‘polio’ infection, is in fact, not.

Talking of streptococci – it is very interesting to note, that in this paper, the authors discovered “an increase in Streptococcus in the moderate arsenic exposure group compared to the low exposure group” – suggesting that this ‘disease-causing bacteria’ is in fact multiplying as the result of exposure to a poison.

In an article published in The Lancet, 1950, the following is reported in relation to the administration of the diphtheria and pertussis (‘whooping cough’) vaccine: “evidence is presented that in the current epidemic of poliomyelitis in Victoria there has been a relation, in a number of cases, between an injection of an immunising agent and the subsequent development of paralytic poliomyelitis.”

Nowadays, such an occurrence would simply be labelled ‘Guillain-Barré syndrome’ (GBS) – which, among other things, is said to be a ‘rare side-effect’ of vaccination. GBS is also mentioned in this must-read paper on the ‘differential diagnosis’ of ‘Acute Flaccid Paralysis’ (AFP) – said to be the the main ‘feature’ of ‘polio’. The authors write that “in the absence of wild virus-induced poliomyelitis, Guillain-Barre syndrome is the most common cause of AFP in many parts of the world”. And furthermore, they also write that “coxsackieviruses A and B, echovirus (54), enterovirus 70 (24, 55), and enterovirus 71 (56-65) have been implicated in polio-like paralytic disease.”

Diphtheria, ‘Japanese encephalitis virus’ and ‘rabies’ are all mentioned, as are so-called ‘non-polio enteroviruses’, for which they write: “non-polio enterovirus infection may be clinically indistinguishable from paralytic poliomyelitis without laboratory studies”.

Talking of Diphtheria, another paper states that “the classic features of diphtheritic polyneuropathy include sensory and motor signs and symptoms, most notably acute flaccid paralysis”.

In the US, a country where ‘polio’ has, apparently, been ‘eradicated’ – ‘non-polio enterovirus’ (NPEVs) are said to cause “10 to 15 million infections” every year. ‘Hand foot and mouth disease’ is said to be one of the symptoms of such an ‘infection’.

‘West Nile Virus’, the “leading cause of mosquito-borne disease in the US”, according to the CDC, is not an ‘enterovirus’ but a ‘flavivirus’ – yet it is said to cause symptoms that “can mimic those of other neurological diseases such as polio or Guillain-Barré syndrome.” Other similar ‘viruses’ include ‘St Louis virus’ and ‘Looping ill virus’.

Moving on to ‘viruses’ that are said to cause distinctive rashes, we are told that ‘scarlet fever’ was previously often confused with ‘diphtheria’ and ‘measles’. In the case of ‘measles’, we are also told that “the measly rash cannot always be distinguished from true measles, instances of which may be mistaken for the initial smallpox rash”.

Physician Al Razi, was the first to describe the symptoms and signs of ‘smallpox’ and ‘measles’. According to his account; “back pain was more severe in smallpox, while it might be slight or absent in measles” and “distress, syncope and anxiety were more prominent in measles.” It is curious to note that the rash – which we are led to believe is quite different for the two – isn’t mentioned once in his ‘differential diagnosis’.

The CDC tell us that ‘smallpox’ was not “reliably distinguished” from ‘chickenpox’ until the end of the 19th century. And the name ‘chickenpox’ has nothing to do with chickens – it was first used by physician Richard Morton (1637-1698) who “characterized it as a mild form of smallpox.”

According to the CDC, ‘lymphadenopathy’ (swollen lymph nodes) is said to be the defining characteristic that sets ‘monkeypox’ apart from ‘smallpox’. However, this symptom is also said to be caused by a number of factors – ‘chickenpox’ being one of them (which we’re told was once thought to be ‘mild form’ of ‘smallpox’). And historically, little attention has been paid to lymph nodes when examining ‘smallpox’ cases.

‘Syphilis’ was confused for smallpox; “when syphilis was first recognized at the end of the fifteenth century it became necessary to distinguish it from smallpox which it occasionally resembled to a most striking degree.”

More recently, we’ve been told about a ‘tomato flu’ outbreak in India, with children said to be suffering of “monkeypox-like symptoms”. It is interesting to note that farmers in the area of the outbreak, were being ‘advised’ to use pesticide dichlorvos on their crops – another toxic organophosphate.

Given all the similarities between these allegedly different ‘pathogens’ – and indeed poisoning – on what grounds do doctors and scientists make the case that these ‘diseases’ are distinct entities, caused by distinct ‘pathogens’?

When asked, the answer one usually gets is this; these ‘pathogens’ have been shown to be different, and to cause the ‘disease’ in question. In short, the similarities are irrelevant; they are caused by different ‘pathogens’.

How is this demonstrated?

In order to demonstrate that a ‘virus’ is the cause of a given ‘disease’, scientists need to follow a sequence of logical steps, which can be summarised as follows:

1.) Isolation & purification

Fluid samples (e.g. sputum) are taken from a sick host. The ‘virus’ particle(s) then need to be isolated and purified from this sample. The isolate should only contain the viral particles and be free from any other contaminants.

It would otherwise be impossible to know whether any deleterious effects observed in future experiments are the result of the particles in question, and not of any contaminants found in the fluids or added thereafter.

2.) Characterisation

The unique biochemical properties of the particle are documented. This is done by taking an electron microscope photo of the new particle(s), after which it can be described, categorised, and its genome sequenced.

3.) Establishing causation

Samples of the newly isolated particle are used in test subjects to try and cause the same ‘disease’. This is so that it can be shown that the ‘virus’ particle is, indeed, the cause of the ‘disease’, and not simply associated with it (like in the example of streptococcus bacteria being positively associated with arsenic exposure).

So-called ‘animal models’, combined with ‘cell culture’ experiments are ‘the norm’. But on occasion, human volunteers are used, and attempts are made to emulate what is said to happen in the ‘real world’ – see for instance the Rosenau spanish flu study, where we are told that “none of the volunteers in these experiments developed influenza”.

This result isn’t unique – in the previously mentioned Rivers paper, he wrote: “Hess and Unger failed to produce varicella in normal children by inoculating them upon the mucous membranes of the nose and throat with vesicle lymph”.

If all the above steps are followed, then, in theory, one could say that a new ‘virus’ has indeed been discovered, and been shown to cause the ‘disease’ being investigated.

In the next article, we will taking a closer look at each of the above steps in more detail, using the not well known – but most interesting – example of the ‘SMON epidemic’ that took place in Japan in the 1960s.

These are not my comments, but I thought them interesting: "Why look for the virus in 1000 people if they didn’t find it in those 3 or 50 people?

They looked at the cytopathic effects like nerds, without control experiments, and then they created the combination of the four letters with computer programs.

And why even bother to look for the virus, or for any pathogenic particle, if contagion between people has never been shown to exist?

First of all, contagion should be proved. They must show if saliva can transmit the illness. This is the most important thing. All the measures are based on the idea of people as saliva shooters. If contagion via saliva is proved, then they could look for something specific in the saliva that is responsible for the transmission of a “virus” [poisonous substance], bacteria, or any fluid or particle. Because saliva of an ill person could be contagious, and if this is the case, they are obliged to find a pathogenic particle.

But if saliva is not contagious, what on earth are we talking about?

It is all about saliva.

The fact that they don’t do experiments with saliva gives us a clue."

Space cowboy says:

June 9, 2022 at 10:37 am

When this scam first started for about a week I made no judgement. Then I learned everyone who died of pneumonia was deemed to have died of “Covid”. The most historically common cause of death was ruled to have been evidence of Covid. The bacteria which precipitate pneumonia are ever present in your lungs. When you get weak enough you succumb to pneumonia. So that’s how you test for a “pandemic”, you declare the most common cause of death to be evidence of a new horribly lethal virus.

Did you already write something about this on twitter or here? https://www.westonaprice.org/health-topics/solving-the-mystery-of-tb-the-iron-factor/#gsc.tab=0