Disclaimer: nothing in this article is to be taken as medical advice. The information provided here is to be used purely for informational and educational purposes.

One of the most common objections to the idea that ‘germs’ do not cause ‘disease’ is; how can we explain the phenomenon of contagion, if not for ‘viruses’ and / or bacteria?

In 1876, Robert Koch discovered the bacteria that allegedly causes ‘anthrax’ (Bacillus anthracis), and in 1882, ‘tuberculosis’ (Mycobacterium tuberculosis). At the time, ‘disease’ was rife, and people were affected by a whole range of conditions that weren’t altogether unknown, but affected greater numbers of people. Setting the scene for us, Thomas Goetz, author of ‘The Remedy’ writes: “to live in the nineteenth century was to experience infectious disease as a constant … a one-hundred-year dirge from one horrid epidemic to another. Six waves of cholera ravaged the globe during the century… there was plague too … yellow fever, influenza, measles – all these pulsed through growing urban populations of the 1800s … Though it had afflicted humanity for millennia, in the nineteenth century tuberculosis went on a rampage, a tide of death known as the White Plague.”

Apparently, this onslaught was caused by growing urbanisation and lack of hygiene – two trends that led to the rapid proliferation of ‘disease-causing germs’, and therefore, ‘disease’. But is there another explanation?

Prior to the advent of ‘germ theory’, the dominant paradigm was ‘miasma theory’ – the belief that ‘miasmas’ or “bad smells” were the cause of people’s ailments. These “bad smells” are said to have affected entire neighbourhoods; “it was obvious; in poor districts, the air was foul and the death rate high. In the prosperous suburbs, no smells – therefore no disease.” Florence Nightingale wrote: “I have known in one summer three cases of hospital pyaemia [sepsis], one of phlebitis [superficial thrombophlebitis], two of consumptive cough [tuberculosis]: all the immediate products of foul air”. Some tried to push for various reforms. For example, the Hungarian scientist Ignaz Semmelweis hypothesised that doctors, after having performing autopsies, carried on them ‘cadaverous particles’ that were the cause of ‘puerperal fever’ (‘childbed fever’). He instituted a policy of using a solution of calcium hypochlorite for washing hands – apparently, because he found that it “worked best to remove the putrid smell of infected autopsy tissue”.

We are thus led to believe that Nightingale, Semmelweis, Pettenkofer and others who didn’t necessarily ‘believe’ in ‘germ theory’, and advocated for improvements to hygiene, did so in order to get rid of these “bad smells”. However, on closer inspection, we find that these were not the only source of concern. Pettenkofer, for instance, was quoted in an article published in Scientific American in 1883, discussing poisoning resulting from coal gas leaks. Based in Munich, he successfully led a series of reforms to the sanitation system that included starting “a running-water system with lead-free tubes”. Pettenkofer is also famous for, at the age of 74 swallowing “an estimated 10⁹ organisms [of Vibrio cholerae] on an empty stomach after neutralizing the acidity in his stomach.” He lived to tell the tale. Some have suggested this was all down to ‘luck’. But he and his students are not the only ones to have ‘tempted fate’ in this way. In this press clipping from the Los Angeles Herald published in 1897, we find that a certain Dr. Thomas Powell appears to have repeated this exact procedure – not just with Vibrio cholerae but with all manner of ‘germs’ – and remained well. According to the article; “the evidence regarding the truth of his claim is conclusive”.

Pettenkofer also took a keen interest in clothing; “to understand the physiological significance of our clothing and its interaction with the skin, he examined clothing material microscopically and analysed its physical properties. This also included searching for poisonous dyes in the clothes. For example, on behalf of the Bavarian Army, Pettenkofer tested anilin blue and black dyes used for military clothes. As it was free of arsenic, Pettenkofer gave its use the green light”.

Poisonous dyes? Arsenic in clothing? In the 19th century, arsenic was “everywhere in the home” – and indeed, this included clothing; “there was an orphanage in Boston and all these small children were getting really, really sick and they didn’t know why. It turned out that the nurses were wearing blue uniforms dyed with arsenic and they were cradling the children, who in turn were inhaling the dye particles.”

Burning coal releases various noxious substances – including arsenic. During the 18th and 19th centuries, coal burning was widespread in England and elsewhere; “increasing demand and falling coal prices led to a rapid increase in national coal consumption, rising from 20 million tonnes in 1820 to 160 million tonnes in 1900 (an eight-fold increase).” London (‘the Big Smoke’), was so polluted, that it “averaged 80 dense fog days per year, with some areas recording up to 180 in 1885 … mortality from bronchitis increased from 25 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants in 1840 to 300 deaths per 100,000 in 1890. At its peak, 1-in-350 people died from bronchitis”.

As discussed previously, arsenic was also used in ‘sheep dip’, which would have eventually made its way into the wool used to make clothes – and indeed, it is worth noting that the highest concentration of arsenic in sheep is found in their wool.

There are also reports of farmers using it to protect their seeds. It is still used to this day as a wood preservative. And it was also used to preserve dead bodies for autopsy. In 1838, physician John Snow wrote a letter published in The Lancet, where he denounced the dangers of this practice, how it could “expose the dissector to breathe an atmosphere contaminated with arsenuretted hydrogen, which is, perhaps the most deadly combination of arsenic”. Going back to Semmelweis – the bacteria said to cause ‘puerperal fever’ are said to be the same as those that caused ‘scarlet fever’; ‘Streptococcus pyogenes’. It is interesting to note that the presence of Streptococcus bacteria has been found to correlate positively with arsenic exposure (see here and here).

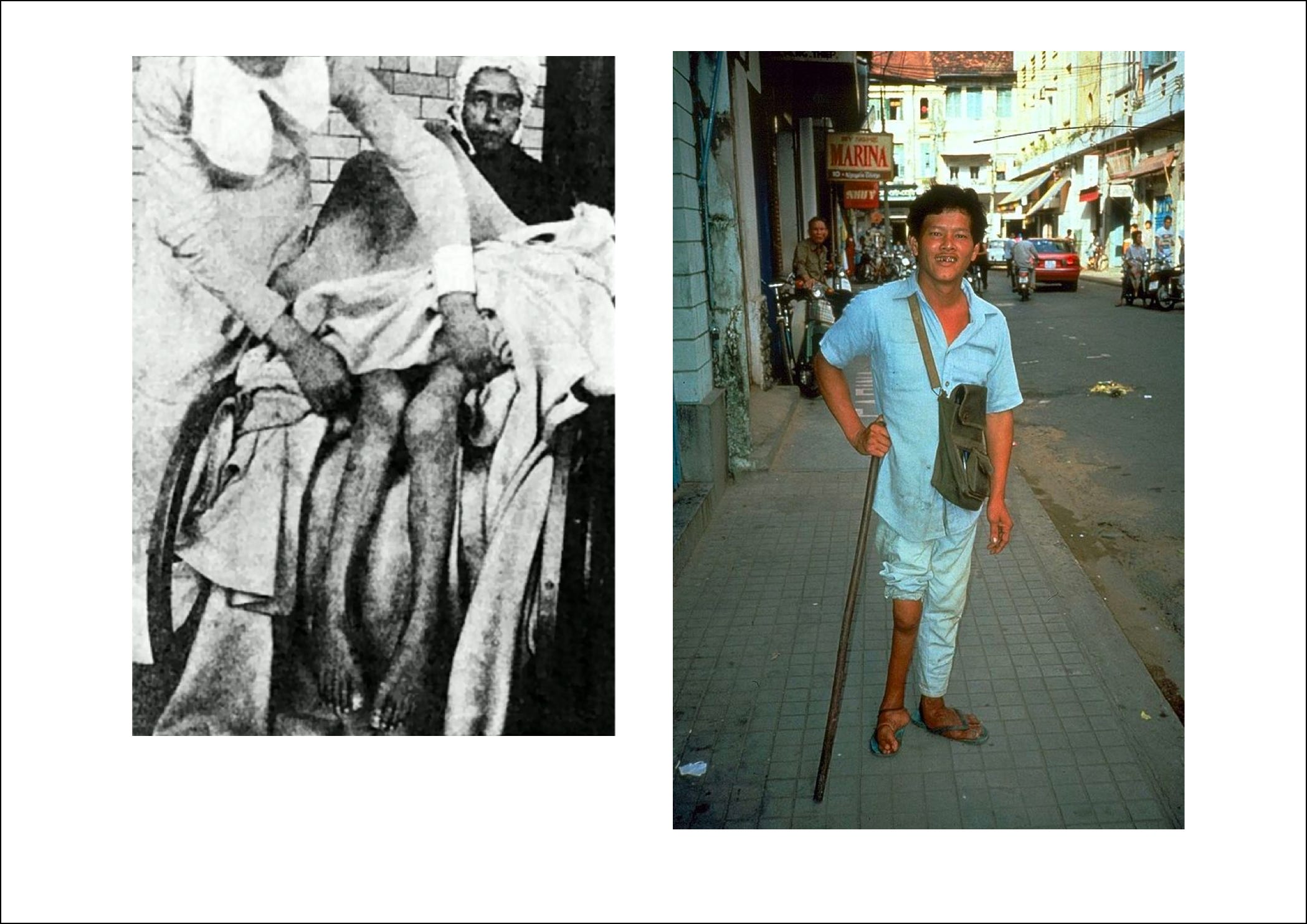

Arsenic was also used extensively in wallpaper; “the French long suspected the British of poisoning Napoleon in his prison on St Helena, by decorating his bedroom with green-patterned wallpaper”. It found its way into baby carriages, candles, plaster, sweets, bread and beer. The symptoms displayed by some of the victims of the 1900 English Beer Poisoning included “complete paralysis of lower limbs with atrophy” (left) – similar to ‘polio’ (right).

And of course, arsenic was also heavily used in pesticides; “the first systematic use of arsenic as a pesticide was in the mid-nineteenth century … A farmer found a potato field had been infested with bugs. They had some Paris Green paint handy and applied it to the patch. A few hours later all the bugs were dead, and a new use had been found for Paris Green … Over the next few decades, many arsenic-based pesticides were trialled. London Purple was used from 1872, which was cheaper than Paris Green and easier to apply. Lead arsenate was used from 1892, which had the advantage of being harmless to plants, and calcium arsenate was adopted for copper crops in the United States in 1906. By 1944, 40 million kg of lead arsenate and around 23 million kg of calcium arsenate was used each year in the United States”.

By the mid-1800s “tuberculosis had reached epidemic levels in Europe and the United States”. This led to the abandonment of “the long, trailing skirts of the Victorian period”, due to the fact “they were thought to harbor tuberculosis microbes”. ‘Tuberculosis’ was particularly prevalent amongst soldiers, due to the ‘disease-causing’ bacteria they were surrounded by. But was that really the problem? The use of poisons in warfare goes back millennia. For instance, we are told that “the first arsenic-based weapon appeared in 431–404 BC when the Spartans used arsenic as a noxious smoke against Athenian-allied cities during the Peloponnesian War.” During the American Civil war (1861 – 1865), all manner of proposals were made for the use of various poisons, which included “using artillery shells charged with arsenic and strychnine”. During the Franco-Prussian war (1870 – 1871), it is said that Napoleon III “proposed the lacing of soldiers’ bayonets with cyanides”. During WWI (1914 – 1918), chemical weapons were widely used – so much so that “the shells contaminated the earth so badly with lead, arsenic and lethal poison gas, France determined that most of the villages couldn’t be rebuilt”. A 2007 study claimed that “the levels of arsenic, used in the detonators, were between 1,000 and 10,000 times the level usually found in the ground”. In short, other than being exposed to all manner of trauma (which we’ll come on to later), these individuals were exposed to enormous amounts of poisons, which no doubt, would have also been present in their food rations and perhaps even water, much of which would have come from metal containers. A report from 1883 mentions “six cases of [lead] poisoning from canned tomatoes”. The issue of canned food being contaminated with toxic metals appears to still be a problem today.

Although ‘tuberculosis’ is said to be caused by a bacteria, it is interesting to note that this bacteria does not appear to always be present; “patients are often negative for acid-fast bacilli staining and culture in spite of having active TB”. As of 2013, scientists still cannot explain how it’s possible for it to survive “for decades in a hostile host environment”. And what’s more, in a recent study (2017), researchers found that “the concentrations of Zinc, Selenium, and Iron were significantly lower in tuberculosis patients; however, that of Arsenic, Lead, and copper was significantly higher”, when compared to the control group. In Chile, 2011, ‘tuberculosis’ shot up “ten years after arsenic leached into the water”. The cases began to drop “following the construction of an arsenic removal plant”.

So to summarise, the idea that ‘miasma theory’ was purely concerned with “bad smells” does not appear to be entirely accurate. It is clear that Pettenkofer at the very least, was fully aware of the dangers that various ‘environmental’ poisons posed to human health.

Now, we’re led to believe that contagion is a readily observable phenomenon – something that everyone has witnessed at least once in their life. But is this really the case?

A poll was shared on Twitter to get some initial data. 59% of people reported never having witnessed such a phenomenon. The qualitative data however, is far more interesting. For the most part, people reported having ‘caught’ colds from others. ‘Hand foot and mouth’ was mentioned by a handful of people, as were ‘stomach bugs’ (e.g. ‘norovirus’), and ‘chickenpox’, ‘measles’ and ‘scarlet fever’.

For obvious reasons, no ‘STIs’ were mentioned, but what was particularly interesting is that no one reported anything more serious – like a case of ‘polio’, ‘ebola’ or ‘tuberculosis’ for that matter. One respondent – a primatologist – also pointed out that he has never seen such a phenomenon in the wild. Only with animals being kept in captivity.

This brings us to an important point; although it is said there are many ‘viruses’ and bacteria involved in all of these ‘diseases’, we often find that the symptoms they cause, are really not all that different. If you look up the symptoms for ‘mumps’, ‘monkeypox’, ‘shingles’, ‘influenza’, ‘ebola’ or ‘polio’ – to take just a few examples – you’ll find that typically, these might include a non-specific rash, fever, chills, a cough, muscular weakness, vomiting, diarrhea, tiredness, headaches and loss of appetite. Some of these are said to have a ‘distinctive feature’; in the case of ‘polio’, this is ‘acute flaccid paralysis’. However, we frequently find that other ‘viruses’, such as ‘West Nile virus’, and even ‘nutritional deficiencies’ cause identical symptoms. ‘Viruses’ that cause rashes are said to be easy to differentiate, due to the difference in their appearance. But all of these seem to get confused for one another. The latest case in point; ‘tomato flu’ mimicking ‘monkeypox’.

Now, all of these symptoms are also said to be found in cases of poisoning, such as what happens with arsenic. To take just one example, here are images taken from a case report showing various family members exhibiting symptoms of chronic arsenic poisoning. The symptoms (left) are not too dissimilar to those of ‘hand, food and mouth disease’ (right).

The report also provides the following images. The black lesions in particular, don’t look all too dissimilar to cases of ‘secondary syphilis’ (top right), or ‘anthrax’ (bottom left).

‘Syphilis’, in some cases (top left), also appears to look like ‘chickenpox’ (here and here), and even another ‘disease’ known as ‘Sweet’s Syndrome’ (bottom left).

As mentioned previously, we also find that ‘polio’ doesn’t look all too dissimilar to cases of arsenic poisoning, or even ‘diseases’ said to be caused by ‘nutritional deficiencies’, such as ‘scurvy’, ‘beri beri’ or ‘pellagra’.

In short, there doesn’t appear to be a single symptom attributed to a ‘virus’ or bacteria, that cannot also be seen in certain cases of poisoning.

What then, is ‘disease’?

Brittanica defines ‘disease’ as “any harmful deviation from the normal structural or functional state of an organism, generally associated with certain signs and symptoms and differing in nature from physical injury.”

Some of these are said to be ‘communicable’, and present themselves through a variety of generic symptoms, which are said to be caused by the ‘pathogen’ in question. Thus, such symptoms are typically thought to serve no real purpose; they are simply the unfortunate result of the activity of the ‘germs’ implicated.

However, fever for instance, has been found to be “a deliberate strategy to bolster our immune defences in the face of infection.” In the case of diarrhea, researchers found that it is “critical to enteric pathogen clearance”. Such findings suggest that the ‘pathogen’ itself isn’t causing the fever or the diarrhea, but that these symptoms are an ‘immune response’ to the presence of one or more toxins. These toxins, for the most part, are discussed in the context of ‘germs’. But the exact same principle applies to any substance the body considers toxic. Going back to arsenic, we find that in some cases, diarrhea described as “rice water like stools” – which are also said to be one of the ‘unique features’ of ‘cholera’, show up. If one has ingested a poison, the body will try to evacuate it as quickly as possible – which may require quite literally ‘flushing it out’. Arsenic is also found in sweat, and even in semen – clearly showing that the body will use whatever means necessary to get rid of it.

What this shows is that the generic symptoms associated with most ‘infectious diseases’ are nothing more than an attempt by the body to rid itself of toxins as quickly as possible. The type of symptom, onset and severity will then depend on things like the dosage, route of exposure, and any existing ‘comorbidities’. If a poison is inhaled, rather than ingested, it is unlikely to trigger diarrhea; instead, a cough or ‘pulmonary infection’ may be the end result. This means we can end up with a wide range of symptom combinations, and the current paradigm will create a new ‘disease’ out of every combination. So, we end up hundreds of different ‘diseases’, caused by hundreds of different bacteria and ‘viruses’. But in reality, as Dr Tilden once put it, there is one ‘disease’ – toxaemia, that simply manifests in different ways, for the aforementioned reasons. The ‘detox process’ can sometimes be accompanied by some discomfort (no one enjoys diarrhea). And sometimes, the ‘purge’ can be too ‘efficient’, and overwhelm the body. This is where Western medicine has its uses; it can help ‘mitigate’ symptoms in cases where doing so may be desirable. But this comes at a cost; one that is perhaps best illustrated by Tilden; “but the disease was not cured; for the cause (enervating habits) is continued, toxin still accumulates, and in due course of time another crisis appears. Unless the cause of Toxemia is discovered and removed, crises will recur until functional derangements will give way to organic disease”.

Going back to our original question; why then do we sometimes see people get sick at the same time, or one after the other?

The first and most obvious explanation is a shared environment. Most people would understand this to mean a shared workspace or home. However, as humans, we all inhabit the same environment, and things that happen even on the other side of the planet may therefore have an impact. Chernobyl and the Minamata bay disaster are both good examples. A similar phenomenon can occur at a more local level; as was seen with ‘polio’. In the 90s, pesticide ‘malathion’ (which the EPA has linked to a whole range of symptoms that are remarkably similar to those of ‘polio’), was sprayed by helicopter over Los Angeles, in an effort to combat ‘medfly’. And just a few years ago, a team of researchers suggested that the ‘disease’ caused by ‘zika virus’, is in fact likely to be linked to the widespread spraying of insecticide ‘Pyriproxyfen’.

Sometimes, toxic substances can be ‘transmitted’ from one person to another due them having been exposed to it; “lead poisoning in children resulting from lead dust unknowingly brought home from work by a member of the household is commonly known as ‘take-home exposure’. Children may also be exposed at home to other metals brought from the workplace apart from lead”. The CDC recommends that protective gear be worn when ‘handling’ animals, to protect themselves from ‘anthrax’, but as noted previously arsenic concentrates in sheep wool. Given the ubiquity of poisons in our environment, it is perhaps no surprise that, on occasion, people get sick at the same time, or soon after one another.

Some say that 95% of the human mind is subconscious. Whether or not this is accurate is another question, but it is clear that a great deal of what goes on in our brain happens without us being aware of it – all bodily processes, which are controlled by the brain, fall in this category. And this means we sometimes mimic others ‘involuntarily’, as seen when yawning, laughing or exhibiting fear.

Let’s now take the analogy of a computer. The computer has various ‘utilities’ that allows the user to initiate a ‘purge’ or ‘detox’. Doing this is essential in ensuring the computer lives a long healthy life, and continues to operate properly. Suppose then that you were, in fact, fully in control of your mind. If a ‘contagious’ disease is nothing more than a ‘detox programme’, then on occasion, we might find ourselves ‘mimicking’ others in an attempt to protect ourselves. Seen in this way, a ‘diseased individual’ acts as a kind of ‘cue’ to let the rest of the ‘herd’ know that something is up, and that some may wish to ‘detox’ preventatively. If we accept the premise that a great deal of what happens in our brains is subconscious, then such a ‘programme’ could be ‘initiated’ without us having ‘launched it’ of our own accord.

All of this also touches on the ideas of another school of thought, known as ‘German New Medicine’ (GNM), which stipulates that symptoms are essentially the end result of a ‘conflict’; “every ‘disease’ - hereinafter called Significant Biological Special Program (SBS) - originates from a DHS (Dirk Hamer Syndrome), which is an unexpected, highly acute, and isolating conflict shock that occurs simultaneously in the psyche, the brain, and on the corresponding organ”. GNM notes however, that “severe malnutrition, poisoning, or an injury can result in the dysfunction of an organ without a DHS”. But there is a case to be made for the idea that the psyche itself can, on occasion cause ‘disease’. The case of the conjoined twins – where one got ‘measles’, while the other didn’t, is a good example. In an article titled “The contagious thought that could kill you”, the BBC provide the following example: “Doctors have long known that beliefs can be deadly – as demonstrated by a rather nasty student prank that went horribly wrong. The 18th Century Viennese medic, Erich Menninger von Lerchenthal, describes how students at his medical school picked on a much-disliked assistant. Planning to teach him a lesson, they sprung upon him before announcing that he was about to be decapitated. Blindfolding him, they bowed his head onto the chopping block, before dropping a wet cloth on his neck. Convinced it was the kiss of a steel blade, the poor man “died on the spot”. A similar phenomenon has been observed in cases of ‘rabies’. Going back to our soldiers from the Franco-Prussian war and WW1, they were exposed to all manner of poisons at the same time – but the synchronicity of the onset of the symptoms, could also be explained by some subconscious phenomenon that is common to all humans; “the biological conflict linked to the lung alveoli is a death-fright conflict because, in biological terms, the death panic is equated with not being able to breathe.” The GNM school of thought also states that; “tubercular secretion, excreted through the sputum, is rich in protein. If the healing phase is long and intense, the protein deficiency could be fatal. Death, however, is not caused by the TB-“infection” but rather by the protein depletion (for that reason, tuberculosis was formerly called “consumption”). This is exactly what happened during the lung tuberculosis epidemic of 1918/19 after millions of people had resolved the death-fright conflicts suffered during four years of war. The end of the war initiated a mass-healing, so to speak, resulting in two pandemics (see also Spanish Flu).”

Some have also suggested that ‘pheromones’ or ‘resonance’ could be involved, although evidence for either phenomenon appears to be lacking. But if we accept the premise that ‘infectious diseases’ are nothing more than ‘detox symptoms’ caused either by exposure to a toxin, or exposure to someone who themselves have been exposed (as a preventative measure), then to a certain extent we might ask; does it really matter?

The fundamental problem here really appears to lie with our outlook. The ‘germ theory’ paradigm has made victims of people and keeps them looking in all the wrong places – it contends that our children, spouse, neighbour, or dog somehow ‘infected’ us, and that we must fear our environment, and those we share it with. In Bangladesh for instance, a region that suffers terribly from chronic arsenic exposure there is a “tendency to ostracise arsenic-affected people, arsenicosis being thought of as a contagious disease”. A similar phenomenon was seen in Japan during the SMON epidemic.

Although we cannot take full responsibility for everything that happens to us health-wise, what this article has hopefully demonstrated is that the only thing we need to be worried about when we bear witness to the phenomenon of contagion, is whether we and others have been exposed to a poison.

Excellent post. I have long suspected that poison especially arsenic is the cause of most 'diseases'.

The human body with the right resources (nutrition) is able to overcome all 'diseases'. The problems occur when 'modern medicine' intervenes by treating the symptoms and interferes with this function.

I also believe that distilled water is an overlooked aid in assisting the body to rid itself of toxins.

Although, as you mentioned, the evidence is lacking, there might be, in fact, some chemosignals (pheromones?) involved in all of this. Not many people know it, but plants "talk" to each other via these three routes:

- by releasing chemicals like volatile organic compounds (VOCs), etc.

- by ultrasonic sounds (frequencies that humans cannot hear)

- via roots system (by secreting chemicals into the soil)

"Plants Emit Sounds Too High For Human Ears When Stressed Out"

https://www.iflscience.com/plants-emit-sounds-too-high-for-human-ears-when-stressed-out-54404

"New research on plant intelligence may forever change how you think about plants"

https://theworld.org/stories/2014-01-09/new-research-plant-intelligence-may-forever-change-how-you-think-about-plants

"Plants May Let Out Ultrasonic Squeals When Stressed"

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/scientists-record-stressed-out-plants-emitting-ultrasonic-squeals-180973716/

"Recordings reveal that plants make ultrasonic squeals when stressed"

https://www.newscientist.com/article/2226093-recordings-reveal-that-plants-make-ultrasonic-squeals-when-stressed/

"Plants Talk. Plants Listen. Here's How"

https://www.npr.org/sections/krulwich/2014/04/29/307981803/plants-talk-plants-listen-here-s-how?t=1658777442204

"Plants 'talk to' each other through their roots"

https://www.theguardian.com/science/2018/may/02/plants-talk-to-each-other-through-their-roots

"Plants Can 'Speak' to Each Other"

https://kids.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frym.2022.658692

"How Plants Secretly Talk to Each Other"

https://www.wired.com/2013/12/secret-language-of-plants/

"Can Plants Talk to Each Other?"

https://sites.nd.edu/biomechanics-in-the-wild/2019/03/06/can-plants-talk-to-each-other/

So it makes sense for animals and humans to possess some similar routes to "share" information apart from visual cues and sounds. And especially when it comes to stress or the potential danger that will send signals for the immune system to "prepare" or "detox", etc.

There is this idea of spreading immunity asymptomatically, which basically means that a strong immune system destroys the "virus" without symptomatic infection, and you now begin spreading immunity by shedding dead viral particles and non-replicable "virus" proteins. Another healthy host then inhales these particles, and his own T cells learn based on that feedback.

"Exposure to SARS-CoV-2 generates T-cell memory in the absence of a detectable viral infection"

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-021-22036-z

What if "detox" and "disease" symptoms (partially) can be induced by chemosignals, and one of the best candidates being pheromones? What if it can be done via several routes like breath (gas exchange), feces, urine, sweat, saliva, etc. ? Nearly all "transmission" happens inside closed spaces anyway. Or alternatively, what if poisons / toxins can be shared (which has already been proven beyond doubt) in the same way? So, in essence, we end up poisoning nearby people with toxins that our bodies try to get rid of?

50% of human sewage is used as fertilizer.

https://twitter.com/EthicalSkeptic/status/1506813194693758978